1917–1918 The United States Joins the Fight

Doing Their Bit—Farming and Food

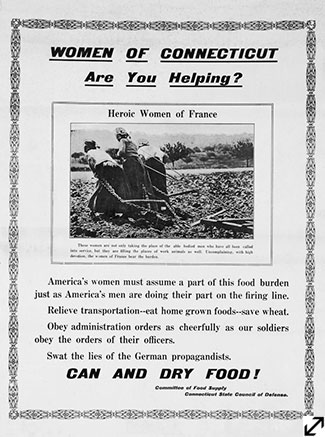

As early as 1914 United States leaders were concerned about the negative impact the War would have upon food supplies in Europe. Once the United States entered the conflict, the urgency was even greater as American men left their farms to fight. Individuals, families and communities were urged to produce, preserve and conserve food stuffs. They tended home and community gardens and they voluntarily restricted the amount of wheat products, meat, sugar and fats they consumed. Devoted gardeners, canners and cooks helped guarantee food supplies for American and foreign military personnel.

Greenwich residents created "War Gardens" in their backyards and public spaces. They established community gardens on great estates, in Bruce Park and on school grounds where students were assigned individual plots. For some in Greenwich, cultivating tomatoes and beans rather than roses was novel, but for many caring for home vegetable gardens was a routine aspect of life, even if not previously pursued with such intensity and patriotic fervor.

Women and Girls Working at the Greenwich Canning Kitchen, c. 1918. Greenwich Historical Society, William E. Finch, Jr. Archives, Town History Collection.

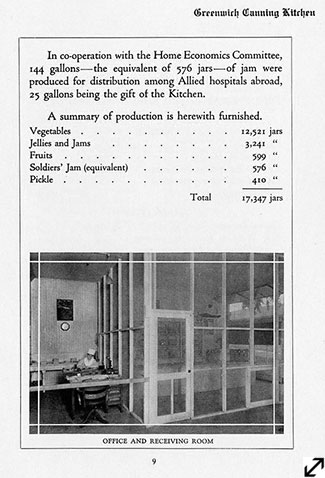

Louisine Havemeyer and other philanthropists in Greenwich established the Greenwich Canning Kitchen as a way to contribute to food coffers. Residents brought in produce to be processed for their own use or for consumption by troops or civilians in need. This program, which operated out of a storefront on Railroad Avenue, was considered a model for other communities.

Thank You Letter from Mrs. Young, October 31, 1918. Greenwich Historical Society, William E. Finch, Jr. Archives, Town History Collection.

Greenwich Canning Kitchen Annual Report, 1918. Greenwich Historical Society, William E. Finch, Jr. Archives, Town History Collection.

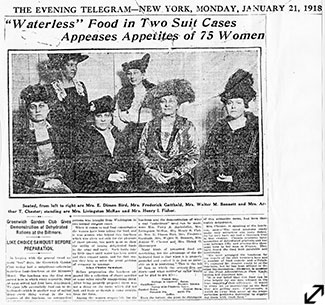

Waterless Food in Two Suitcases Appeases Appetites of 75 Women. Reproduction of article in The Evening Telegram, New York, January 21, 1918. Greenwich Historical Society, William E. Finch, Jr. Archives.

Members of the Greenwich Garden Club, including Constant Holley MacRae (upper right), carried the makings of a model dehydrated meal with patriotic undertones to Washington, D.C. where they served it to government officials and others. They wanted to show how the dehydrated "rations" they had created would make it possible for all American service personnel, no matter where they were stationed, to enjoy a tasty Thanksgiving feast. During the Great War years, partaking of a Thanksgiving meal was a meaningful ritual for military men, expressive of the American values for which they fought and the importance of the struggle which separated them from their loved ones.

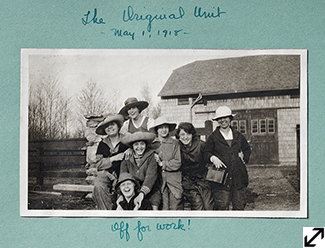

The Farmerettes of Sabine Farms, 1918. Photograph album Greenwich Historical Society, William E. Finch, Jr. Archives, Gift of the Family of Henry J. Fisher.

Woman's Land Army of America or the Farmerettes

Maximizing agricultural production was seen as central to winning the War. The women who signed up to take the place of male farmhands were nicknamed “Farmerettes.” Championed by Greenwich’s own Louisine Havemeyer and Caroline Ruutz-Rees among others, the organization hosted a training camp in nearby Bedford, New York. Participants, ages 18 to 40, were paid $2.00 per day for eight hours labor. The college girls and socialites who worked as farm laborers considered it a patriotic adventure. Women and girls in the farming families generally found the work more routine than exciting.

The Farmerette program stands as one example of how the War broke down gender barriers. Even the trousers and overalls the women wore spoke of a new freedom. In the 1920s, changes for women included winning the right to vote as well as the flapper lifestyle with its less constricting dress and social code.

The Hartford Courant reported on May 4, 1918, that 10 Farmerettes from New York and New Jersey, "the advance guard of a division of the woman's grand army," had arrived at the Henry J. Fisher farm "equipped with overalls and other articles of farm costume." They would work on the Fisher, Baldwin and Flagler farms.